From stamps to a $5.5 billion industry - An Overview of Gamification

From air miles to loyalty cards to exclusive concert tickets, gamification is all around us. With the potential to increase revenue, change behaviour and improve health, let us take an in-depth look at how gamification can be implemented to change the world around us for the better. All thoughts, views and comments are my own.

What is Gamification?

Gamification is the technique of applying game mechanics to non-gaming applications with the aim to promote user adoption and increase user engagement. If implemented correctly, the same set of mechanics can be applied to many diverse sectors to extract business benefits such as increasing brand awareness, ensuring customer loyalty and collecting key metrics for future refinements. Although there is no single set of defined gamification techniques, they all strive for the same ultimate goal of increasing engagement. “When you turn work into a game, it becomes engaging” and when people are engaged, they are motivated, feel inspired and ready to compete (Jones, 2015).

Significant Moments in History

The history of gamification dates back to almost a decade before the Wright brothers invented the first gas motored and manned airplane. Even at this time, marketers were investigating ways to arouse loyalty in their customers. One of the earliest signs of gamification can be traced back to 1896 when stamps were first used to reward trustworthy customers. Over a century later, brands, companies and people are still exploring methods to positively reinforce buyer behaviour and engagement in an industry that is now worth almost $5.5 billion (Turco, 2017). The following outlines the most significant moments in gamification history:

- 1896: S&H Green Stamps. Marketers sold stamps to retailers who used them to reward loyal customers.

- 1973: Charles Coonradt founds a consulting firm called “The Game of Work,” and brings feedback loops found in sports into the workplace.

- 1979: MUD1 is created by Roy Trubshaw at Essex University. It was the first multi-user virtual world game.

- 1980: Thomas Malone publishes “What Makes Things Fun to Learn: A Study of Intrinsically Motivating Computer Games”.

- 1981: American Airlines introduces AAdvantage, the first frequent flyer program.

- 1983: Holiday Inn launches the first hotel loyalty program.

- 1987: National Car Rental launches the first car rental rewards program.

- 1990: 30% of American households own an Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). A new generation of gamer is born.

- 1996: Richard Bartle publishes “Who Plays MUAs” which divides video game players into four unique types.

- 2002: Serious Gaming Initiative forges a link between the electronic gaming industry and training, health, education and public policy.

- 2003: Nick Pelling coins the term gamification.

- 2007: Bunchball creates Dunder Mifflin Infinity, a gamified website for the TV show The Office. It receives over 8 million page views in six weeks.

- 2009: Quest To Learn accepts a class of 6th graders into a game-based learning environment.

- 2010: DevHub adds a points system to its website, and increases user engagement by 70%.

- 2010: Gamification Co. holds the first Gamification Summit in San Francisco, CA.

- 2012: 45,000 people enroll in Professor Kevin Werbach’s online gamification course through Coursera.

- 2012: Mozilla Open Badges initiative is launched. The open source badges can be used to mark accomplishments online.

- 2012: Gartner predicts 70% of Global 2000 organizations will have at least 1 gamified application by 2014.

- 2013: 61% of surveyed CEO and other senior executives say they take daily game breaks at work.

- 2014: 90% of companies report their gamification efforts are successful.

- 2016: Gamification is a $2.8 billion industry.

- 2018: Gamification is predicted to be a $5.5 billion industry.

Gamification Deconstructed

Model Essentials

There are many interpretations of how a gamification model should be applied, but in general, for a gamification model to become successful, it must consist of the following (Chang, 2012):

- Goals: Goals should be presented to the user in ascending order of difficulty with a clear outline of what is required to complete each one.

- Real-Time Scoring and Feedback: On successful completion of any goal or milestone, the user should receive an immediate positive notification awarding them with a sense of gratification for their progress.

- Competition Transparency: Current ranking, progress and conditions for goal completion should be visible to the user at all times.

- Rewards: Rewards, both implicit (e.g. money) and explicit (e.g. badges), should be awarded to the user for their performance. However, it is important to note that the higher or greater the reward does not always correlate to the greater the effort (Rimon, 2015).

Emotional Elements

To further strengthen user adoption, the most successful gamification models put an emphasis on emotion (Porter, 2012). The following emotional components (Lazzaro, 2004) have been proven to create deeper engagements by solidifying the user’s connection to the experience.

- Make It Challenging (Hard Fun): This is for people who like the opportunity to challenge themselves and put their capabilities to the test. By designing a structured experience where the skill level is balanced to the goal difficulty, the user feels a greater sense of accomplishment once an obstacle has been overcome or a demanding goal is achieved.

- Include Novelty (Easy Fun): This is for people who focus on the enjoyment of taking part. By creating goals that can be achieved by exploring, the sensations of mystery are created which immerse the user within the involvement of curiosity and intrigue.

- Provide Friendship (People Fun): This is for people who gain more from social interactions. By providing the option of pursuing common goals, the desire for recognition is enhanced by the amusement and addiction of sharing experiences.

- Add Meaning (Serious Fun): This is for people who treasure their internal sensations and treat their experiences as therapy. By forming a meaningful purpose by combining perception and behaviour, a person’s emotions can be transformed resulting in mundane tasks becoming enlivened.

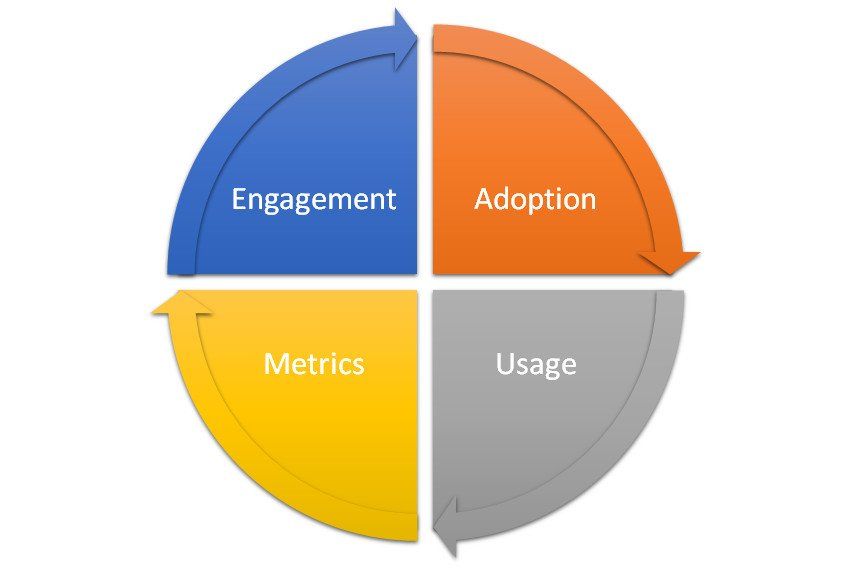

Life Cycle

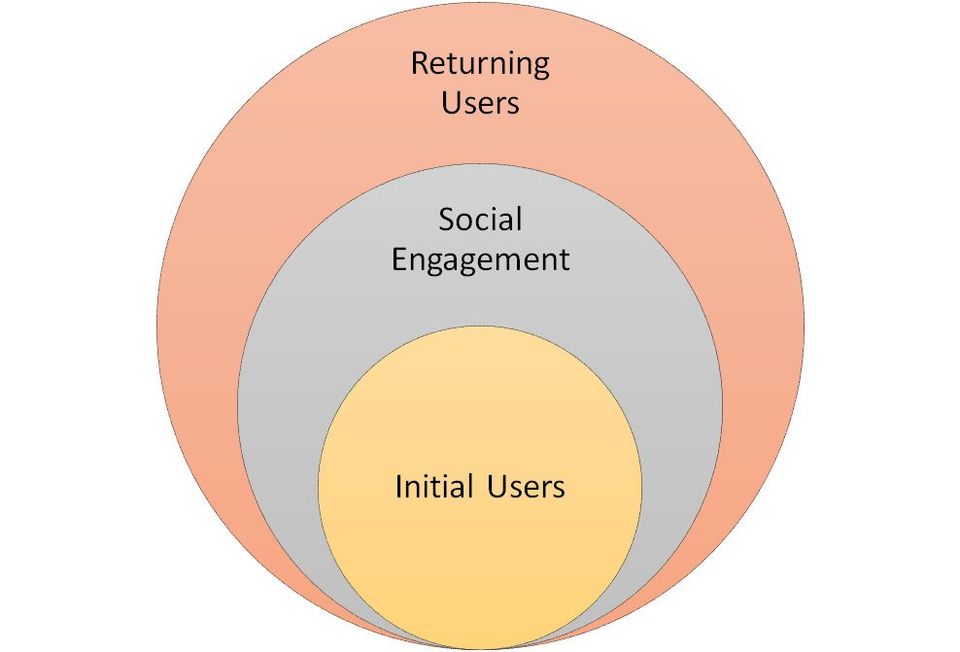

It can be seen that there is no distinct model for implementing gamification, however, a life cycle has been defined in which the modular gamification building blocks should be aligned (Rangaswami, 2012).

- Engagement: Users are drawn in with the promise of reward. They are initially presented with achievable challenges that result in almost instant gratification.

- Adoption: Belief of the model which entices the users to make the commitment of time and effort in exchange for bigger rewards.

- Usage: Mass acceptance of the model resulting in a growth of returning users and the development of hard-core/addicted users.

- Metrics: Business benefits are generated based on the analysis from the data collected. Game mechanics can be tweaked at this point to maximise user engagement and increase business value.

User Psychology

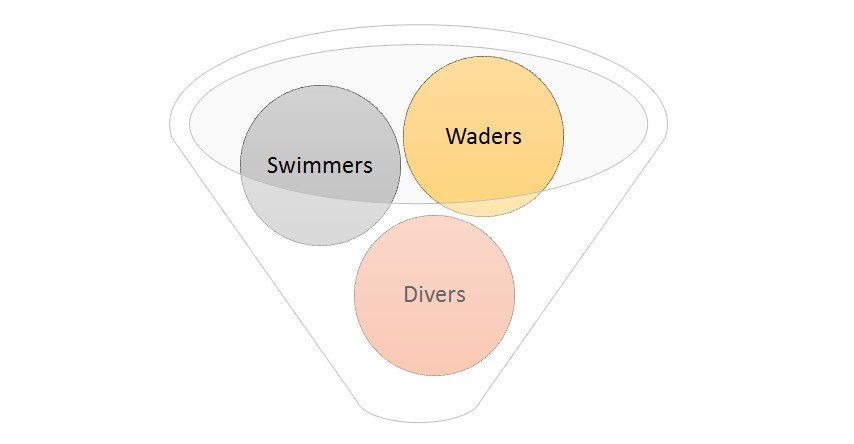

Within any gamification model, regardless of the building blocks of which it has been constructed, it is imperative to consider and cater for all abilities. Theme-park ride designer David C. Cobb uses a swimming analogy to understand the different types of users for any gamified system (Cobb, 2012).

As a single user could potentially move between all user types, a successful model must accommodate all types making sure not alienate any users. “It’s an engagement pyramid, and you’re trying to seduce people up the pyramid” (Martin, 2017).

- Waders: The average user who does not want to spend too much time but still wants to enjoy the experience.

- Swimmers: The user who wants to try new things and interact.

- Divers: The user who wants to achieve every goal possible.

Looking deeper into the psychology of how these user types play games, Richard Bartle has developed a test which classifies users into four categories based on what they enjoy most when playing games (Bartle, 2008). Conducting detailed player research will help you understand which user types may dominate your environment and help you incorporate features in your design to facilitate these (Kumar, Herger and Dam, 2017).

- Killer: Accounting for approximately 1% of users, killers are motivated by competition with their main aim to cause as much grief as possible to other users and see them lose. Achieving is only necessary in order to become powerful and discover creative ways to eradicate other users. They only revert to socialising and exploring as ways to antagonise other users.

- Achiever: Accounting for approximately 10% of users, an achievers ultimate aim is to gather as many points/rewards as possible in order to progress through the ranks. Achievers typically respond well to incentive schemes. They will only kill when it is necessary to eliminate rivals. Socialising and exploring are only used as methods to gain knowledge from other users and discover new ways of collecting points.

- Socialiser: Accounting for approximately 80% of users, socialisers relish interactions with other users. Their pleasure comes from communicating, empathising and observing other users in order to build lasting relationships. They will only kill as an act of revenge. Achieving is required when the need to boost their status in the community arises and they will only explore in order to understand what others are doing.

- Explorer: Accounting for approximately 10% of users, explorers enjoy discovering the unknown within esoteric scenarios. Killing is considered to be too much hassle, but they will aim to achieve and socialise in order to enter the next phase of the adventure and source new ideas.

Design Patterns - How to Implement Gamification

The gamification elements outlined previously can be applied to the user journey to create repeatable design patterns that promote play and play-like engagement (Direkova, 2012).

Designing for Initial Users

Arguably the most important aspect of any system is the beginner experience. An opinion is formed during this initial interaction on whether they enjoy the experience and will possibly return to use at a later stage. If the system provides inconsistent feedback or the goals are not transparent, the user may lose their trust in the system (Reeves, 2012). The aim here is to generate vast interest upfront and help the user understand how you are making their life better.

“You cannot over-reward the player in the first 10 minutes”– Sid Meier, Civilization Designer

- Visual Storytelling: When providing core instructions to the user, visual images are more effective than long explanations described using plain text.

- Tutorials: Transparency and faith in the system can be achieved by guiding the user with visual cues and easy to follow information on system functionality. An open facility where users can ask questions can minimise frustration if they deem the tutorials or manuals to be insufficient.

- Rewards: Introductory rewards provide the user with almost instant gratification and serve as an initiation into the rewards system. Clear visibility on what is required to achieve all rewards should be presented to the user.

Designing for Social Engagement

Most gamification systems utilise a reward system whereby the users gain rewards for completing tasks within a system. However, if the system is not significantly complicated, there may be a limited set of tasks, therefore leading to a limited set of rewards to achieve. As a consequence, most systems, where possible, utilise social networks. It has been proven that the range of positive emotions and amusement grows when users are playing games within a social context (Lazzaro, 2004).

- Forming Teams: Teams give people a sense of community and support. Providing the ability to collaborate towards achieving common goals, encourages people to perform better and more efficiently.

- Sharing milestones: As shared achievements require more than one user to accomplish, the interactions between users become more meaningful.

- Social Feedback: Social feedback mechanisms such as ratings, comments and approvals, nurture social behaviour. To control communication, structured feedback can be put in place to eliminate negative connotations.

- Reputation: Allow transparency of all users reputations within the system. A users reputation inevitably grows as they participate within a community. Building on their reputation stimulates engagement and allows them to become internally invested and establish their value among their peers.

Designing for Retention

For any system to succeed, adoption and retention levels must be high. If users are not participating and returning to the system, the benefits of gamification will diminish. Obtaining new users can be 25 times more expensive than retaining existing users. Increasing user retention by just 5% can lead to boosting profits up to 95% (Reichheld and Schefter, 2000). The initiative fatigue, which is the gradual fade of a users participation after a deployment of initiatives, is approximately 100 days (Kim, 2012). To tackle this phenomena, users must be given a reason to stay engaged and initiatives must be refreshed and updated to compliment this.

- Leaderboards: Score can be used to influence behaviour in a powerful way. Users gain pride and identity towards their score, leading them to seek new ways to grow and improve their statistics. Remarkable user achievements should be publicised giving all users the opportunity to gain reputation with their associates. To avoid alienating users of different abilities, users should be grouped based on similar competencies and displayed on divisional leaderboards.

- Content Unlocking: Users should be aware that new content is available based on achieving a particular set of goals. Users should be awarded for their extra effort with an upgrade in their status and given a new range of possibilities. These challenges should be novel as users react more positively to unique and personalised content (Chamillionaire, 2012).

- Loyalty Incentives: As existing users spend 67% more than new customers and contribute to almost 40% of online shopping revenue (Bernazzani, 2017), loyalty schemes should be introduced. Frequent users should be rewarded with merchandise, discounts, coupons or even rare pre-release products as a compliment to their positive experience and satisfaction of the product/service.

Real-Life Implementations

Gamification techniques can be applied to many different sectors in order to change peoples behaviour for the better by turning ordinary tasks into fun challenges.

Health & Safety

Nevena Stojanovic from Serbia created the “Play Belt” project for The Fun Theory, a 2009 initiative from Volkswagen, with the aim to try and encourage people to wear their safety belt while driving. When the person sits in the car, they will be given instructions on how to fasten their safety belt. The in-car entertainment system can only be used once the safety belt has been successfully fastened.

Kevin Richardson from USA created the “Speed Camera Lottery” project for the Fun Theory with the aim to try and encourage people to obey the speed limit. As a car successfully drives within the speed limit, they will be entered into a lottery to win the total amount accumulated from the fines of all the cars who disobeyed the speed limit. The average speed decreased by 22% from 32kph to 25kph during a three day period.

“Piano Stairs” was a project that was entered into The Fun Theory with the aim to encourage more people to take the stairs rather than the escalator or elevator. During the experiment, results showed that 66% more people chose to use the stairs rather than the escalator.

Environmental

San Diego middle school set up a local challenge where people can compete against each other to win prizes by saving energy. Through this program, participants saved an average of 20% of their total energy costs (Shaw, 2012).

“Bottle Bank Arcade” was a project that was entered into The Fun Theory with the aim to encourage more people to recycle their glass bottles. For each of the holes associated with the bottle bank, a light above will indicate what hole the bottle should be placed. The user will receive points if they insert the bottle into the correct hole. During the experiment, results showed that this bottle bank was used more than 50 times more than a nearby conventional bottle bank.

“The World’s Deepest Bin” was a project that was entered into The Fun Theory with the aim to encourage more people to throw their rubbish into the bin. During the experiment, results showed that the rubbish in this bin weighed 41kg more than a nearby conventional bin.

“Ballot Bin Voting Ashtray” was an initiative from Hubbub Campaigns that aimed to encourage people to place their cigarette butts into a voting ballot box asking everyday general questions rather than dispensing them on the streets.

Education & Training

Research conducted by Traci Sitzmann at the University of Colorado proved the effectiveness of games within the educational field. If gamification is applied to studying, the average scores for learning factual knowledge increased by 11%, skills acquisition increased by 14% and retaining knowledge increased by 9% (Sitzmann, 2011).

Impressive results can be achieved by combining fun, engagement and old fashioned teaching along with the right amount of enthusiasm (Zichermann, 2012). In 2012, Tim Vandenberg, a Monopoly expert and 6th grade teacher from California, turned the popular board game into an educational tool to inspire and motivate his students to obtain perfect scores on their maths examinations by mastering key skills such as mathematics, economics & social negotiation (Vandenberg, 2012).

In 2012, AT&T teamed up with GameDesk for an initiative to embed academic content and assessment into fun and interactive digital games and simulations, making them widely available to parents, students and educators. One game aimed to teach students aerodynamics, not through mathematical equations, but by allowing them to fly their own bird using a gaming simulation where aerodynamic forces were explained during the gameplay (Shiroishi, 2012).

Workplace

Many of our toughest goals require gruelling effort, difficult lifestyle changes and a great deal of persistence. However, because goals are purpose driven and complex, they are the perfect place to begin experimenting with self-gamification as a means to feel more motivated and engaged with life. Jonathan Guerrera gamified his habits and organised his time by using post-its, awarding himself positive and negative points towards tasks with the goal of receiving achievements (Kuo, 2017).

Game mechanics can also be incorporated into the work place in order to inspire colleagues, enhance culture and increase employee retention, engagement and productivity. RedCritter developed a gamified project and team management solution (i.e. RedCritter Tracker) which gives real-time project feeds for multiple projects and teams, badges and rewards for accomplishments, interactive progress reports and automatic time tracking of tasks (Griffith, 2011).

Google launched a travel expense gamification system to encourage employees to submit their expenses on time. This system allowed employees to choose what happened to the remaining money from their allowance during work trips. Within six months of launching the program, all employees were 100% compliant (Coy, 2015).

Hewlett Packard launched Project Everest, a game-based reward scheme website, to give holidays and other prizes to their best reseller teams, resulting in a 56.4% and $1 billion increase in revenue (Enterprise Gamification, 2017).

Science

Crowdsourcing is an important aspect that embraces the power of the community by combining the intelligence of humans and the power of computers to solve problems that neither could solve alone. In 2011, a game called FoldIt turned to crowdsourcing in the attempt to unlock the secret structure of an Aids-related enzyme that the scientific community has been unable to unlock for over a decade. The game allowed users to manipulate protein shapes in order to gain points for correct sequences. Using the collaboration of 40,000 people during a 10 week period, the online puzzle, combining brain and computational power, solved the 15 year problem (Cooper, 2012).

The XPRIZE Foundation is an educational non-profit organization whose mission is to facilitate radical breakthroughs for the benefit of humanity. Their aim is to inspire the formation of new industries and the revitalisation of markets that are currently stagnant due to existing failures or a commonly held belief that a solution is not possible. The foundation addresses the world’s Grand Challenges by creating and managing large-scale, high-profile, incentivized prize competitions that stimulate investment in research and development (R&D) worth far more than the prize itself. The competitions are split into four Prize Groups: Education & Global Development, Energy & Environment, Life Sciences and Exploration. It motivates and inspires brilliant innovators from all disciplines to leverage their intellectual and financial capital (XPRIZE, 2017).

Software

Founded in 2001, TopCoder, a company that administers contests in computer programming, developed a model for crowdsourcing software development which allowed members of a global community to compete against each other for the right to work on client projects. Corporate clients are connected to the world’s top technical talent consisting of over 1 million members located in almost every country around the globe. Over 7,000 online competitions are hosted every year to the world’s largest community of competitive designers, developers and data scientists (TopCoder, 2017).

In January 2012, Microsoft released an achievements extension for Visual Studio 2010 to introduce progress, achievements and fun into their widely-used technical platform. By monitoring software developer performance, users can be encouraged to adhere to correct coding standards by earning achievements.

StackOverflow created a collaborative tool, whereby the community collectively solve complex problems online. Now the largest online community for developers to learn and share their programming knowledge, users can build up a trust level where they can gain badges and are exposed to additional features. User engagement will directly shape what forums will be developed in the future (Attwood, 2012).

Travel

The majority of airlines have now implemented tiered achievement levels to encourage people to earn points as they travel. These points can then be used in order to receive and exchange for benefits. Outcomes have shown that people will purchase more expensive tickets and even take non-direct flights in order to gain mileage points (Saranathan, 2012).

Conclusion

Gamification is changing the face of the modern social enterprise and will soon become widely adopted as good design practice (Chang, 2012). Applying game design strategies to business environments requires a fundamental understanding of that business’ objectives and audience. Game mechanics, reputation mechanics and social mechanics can all be deployed across websites and business applications to increase the adoption of technology as well as customer loyalty and engagement. When coupled with the power of the community, tremendous results can be achieved. Competition has been proven to be one of the key ingredients that drives creative achievement and innovation (Sampanthar, 2012). Studies show that when competition is introduced, almost 50% of people benefit (Merryman and Bronson 2014) and R&D spending’s increase resulting in more valuable patents and breakthrough innovations (Li and Zhou, 2015).

Industry experts state that interactive learning can strengthen retention by up to ten times normal learning approaches (Paycor, 2017). In 2016, 45% of the Global 1000 organisations used gamification as the primary mechanism to revitalise business operations. Over 50% of technology stakeholders propose that gamification will be widespread by 2020 and at present, over 61% of CEO’s take regular game breaks at work, with over half believing that it helps them be more productive (Designing Digitally, 2017).

In situations where gamification has not yet been implemented, 89% of e-learners think they would be more engaged if a point system was proposed, 80% of the workforce feel they would be more productive if work was more like a game and 60% of people think they would be more motivated if leaderboards and competitions were introduced (Designing Digitally, 2017).

It is clear to see that immense potential exists for integrating gamification elements within many diverse sectors. By using the techniques of gamification along with behavioural design, gamification holds a positive promise for changing the future by increasing knowledge, enhancing education and improving health. In relation to user devotion, the average consumer is involved in 14 loyalty programs but only have the capacity to engage with 7 (Loyalty, 2017). Howard Schneider, senior consultant for Kobie Marketing, states that companies should look beyond convoluted reward schemes and start offering additional benefits and value as part of their loyalty programs (Hyken, 2017). Gamification holds the key in the future of marketing, making the workplace a more enjoyable environment, making people better versions of themselves and increasing education and awareness to allow people to reach their maximum potential (Zichermann, 2012).

References

- Attwood, J. (2012). Stack Overflow and Stack Exchange: Programming the Programmers. GSummit. San Francisco.

- Bartle, R. (2008). Richard A. Bartle: Players Who Suit MUDs. [online] Mud.co.uk. Available at: http://mud.co.uk/richard/hcds.htm [Accessed 2 Nov. 2017].

- Bernazzani, S. (2017). Customer Loyalty: The Ultimate Guide. [online] Hubspot. Available at: https://blog.hubspot.com/customer-success/customer-loyalty [Accessed 3 Nov. 2017].

- Bronson, P. and Merryman, A. (2014). Top Dog: The Science of Winning and Losing. North Sydney, NSW: Ebury Austrailia.

- Cobb, D. (2012). The Magic of the Real World. GSummit. San Francisco.

- Cooper, S. (2012). Solving Hard Problems with Gamification and Crowdsourcing. GSummit. San Francisco.

- Coy, C. (2015). 5 COMPANIES USING GAMIFICATION TO BOOST BUSINESS RESULTS. [online] Rework. Available at: https://www.cornerstoneondemand.com/rework/5-companies-using-gamification-boost-business-results [Accessed 3 Nov. 2017].

- Chamillionaire. (2012). Direct to Fan Engagement. GSummit. San Francisco.

- Chang, T. (2012). The Investment Case for Gamification: Opportunities and Threats in the Next Five Years. GSummit. San Francisco.

- Designing Digitally. (2017). Gamification Statistics - Survey Data, Elements and Growth. [online] Available at: https://www.designingdigitally.com/infographics/gamification-statistics-survey-data-elements-statistics-and-growth [Accessed 3 Nov. 2017].

- Direkova, N. (2011). Game on: 16 design patterns for user engagement. [online] SlideShare. Available at: https://www.slideshare.net/nadyadirekova/game-on-16-design-patterns-for-user-engagement [Accessed 1 Nov. 2017].

- Enterprise Gamification. (2017). Facts & Figures - Enterprise Gamification Wiki. [online] Available at: http://www.enterprise-gamification.com/mediawiki/index.php?title=Facts_%26_Figures [Accessed 3 Nov. 2017].

- E-Learning Infographics. (2014). A Brief History of Gamification Infographic. [online] Available at: https://elearninginfographics.com/brief-history-of-gamification-infographic/ [Accessed 2 Nov. 2017].

- Griffith, T. (2017). RedCritter Tracker: Gamifying agile project management. [online] Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/idUS246241602620110722 [Accessed 2 Nov. 2017].

- Hyken, S. (2017). The Best Loyalty Programs Go Beyond Rewards. [online] Forbes.com. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/shephyken/2017/03/25/the-best-loyalty-programs-go-beyond-rewards/#311f6a772503 [Accessed 3 Nov. 2017].

- Jones, L. (2015). Competition the key to employee motivation and customer engagement - Engage Employee. [online] Engage Employee. Available at: http://engageemployee.com/competition-the-key-to-employee-motivation-and-customer-engagement/ [Accessed 31 Oct. 2017].

- Kim, C. (2012). Enterprise Gamification of Fitness: From 10% to over 75% Regular Workouts. GSummit. San Francisco.

- Kumar, J., Herger, M. and Dam, R. (2017). Bartle’s Player Types for Gamification. [online] The Interaction Design Foundation. Available at: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/bartle-s-player-types-for-gamification [Accessed 2 Nov. 2017].

- Kuo, I. (2017). How to Gamify Your Goals: A Step By Step Guide - Gamification Co. [online] Gamification Co. Available at: http://www.gamification.co/2013/01/02/how-to-gamify-your-goals-a-step-by-step-guide/ [Accessed 2 Nov. 2017].

- Lazzaro, N. (2004). Why We Play Games: Four Keys to More Emotion Without Story. XEODesign. [online] XEODesign. Available at: http://xeodesign.com/xeodesign_whyweplaygames.pdf [Accessed 31 Oct. 2017].

- Loyalty, B. (2017). The Loyalty Report 2017. [online] Info.bondbrandloyalty.com. Available at: https://info.bondbrandloyalty.com/2017-loyalty-report [Accessed 3 Nov. 2017].

- Li, X. and Zhou, Y. (2015). Does Import Competition Spur Innovations? [ebook] Ross School of Business. Available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2701645 [Accessed 31 Oct. 2017].

- Martin, J. (2017). A Theme Park Designer Tries to Imagine Nintendo Land. [online] Waypoint. Available at: https://waypoint.vice.com/en_us/article/9a4ygy/a-theme-park-designer-tries-to-imagine-nintendo-land [Accessed 1 Nov. 2017].

- Paycor. (2017). Gamification Trends in eLearning. [online] Available at: https://resources.paycor.com/blog/infographic-gamification-trends-in-elearning [Accessed 3 Nov. 2017].

- Porter, D. (2012). Come for the Game, Stay for the Community: Building and Sustaining Lasting Engagement Online. GSummit. San Francisco.

- Rangaswami, J. (2012). Engage Employees and Drive Innovation with Gamification. GSummit. San Francisco.

- Reeves, B. (2012). Games That Change the Nature of Work: Lessons in Making and Implementing Productivity Games in the Enterprise. GSummit. San Francisco.

- Reichheld, F. and Schefter, P. (2000). The Economics of E-Loyalty. [online] HBS Working Knowledge. Available at: https://hbswk.hbs.edu/archive/the-economics-of-e-loyalty [Accessed 3 Nov. 2017].

- Rimon, G. (2015). It's Not About the Cash: Insight on Employee Engagement. [online] Gameffective. Available at: https://www.gameffective.com/cash-and-employee-engagement/ [Accessed 31 Oct. 2017].

- Sampanthar, K. (2012). Motivational GPS: Understanding the Science of Motivation. GSummit. San Francisco.

- Saranathan, K. (2012). Reinventing Loyalty: How Gamification Reshapes Consumer Marketing. GSummit. San Francisco.

- Shaw, P. (2012). Gamification to Drive Smart Energy Behaviors. GSummit. San Francisco.

- Shiroishi, B. (2012). Gamification for Social Good: Learning from AT&T. GSummit. San Francisco.

- Sitzmann, T. (2011). A META-ANALYTIC EXAMINATION OF THE INSTRUCTIONAL EFFECTIVENESS OF COMPUTER-BASED SIMULATION GAMES. Personnel Psychology, [online] 64(2), pp.489-528. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01190.x/abstract [Accessed 2 Nov. 2017].

- Topcoder. (2017). Deliver Faster Through Crowdsourcing | Topcoder. [online] Available at: https://www.topcoder.com/ [Accessed 2 Nov. 2017].

- Turco, K. (2017). Infographic: The History of Gamification. [online] The History of Gamification. Available at: http://technologyadvice.com/blog/marketing/history-of-gamification-infographic/ [Accessed 2 Nov. 2017].

- Vandenberg, T. (2012). Monopoly Academy: Winning the “Game” of No Child Left Behind through Gamification and Monopoly, the World’s Most Famous Board Game. GSummit. San Francisco.

- XPRIZE. (2017). XPRIZE. [online] Available at: https://www.xprize.org/ [Accessed 2 Nov. 2017].

- Zichermann, G. (2012). Gamification: What’s Next? GSummit. San Francisco.