Why You Should Thank Leonardo da Vinci - An Overview of User Experience (UX) Design

User experience (UX) is all around us, but where did it come from? Let us take a look at what UX design is, the origin dating back to Leonardo da Vinci, the progression over time, an understanding of how it can be broke down into its simplest elements and finally some statistics on how UX can add value to your business. All thoughts, views and comments are my own.

What is User Experience?

Humans inherently take different experiences from interactions, therefore user experience (UX) is aimed at tailoring a specific set of experiences and promoting certain behaviours when users interact with interfaces (Strike, 2015). As UX is an elusive concept, several definitions exist based on studies, theories, discussions and research. The ISO guidelines (ISO 9241-210) in ergonomics of human-system interaction, specifically human-centered design for interactive systems, describes UX as a “person's perceptions and responses resulting from the use and/or anticipated use of a product, system or service” (ISO, 2016). This definition still emits personal interpretation and therefore three additional notes are presented to accompany this single definition with the aim to further help explain that the notion of UX pretty much encompasses the entire experience and journey of a user before, during and after attempting to perform tasks. Matthew Magain and Luke Chambers describe UX in their book ‘Get Started in UX’ as “the what, where, when, why and how someone uses a product, as well as who that person is” (Magain and Chambers, 2014).

History of User Experience

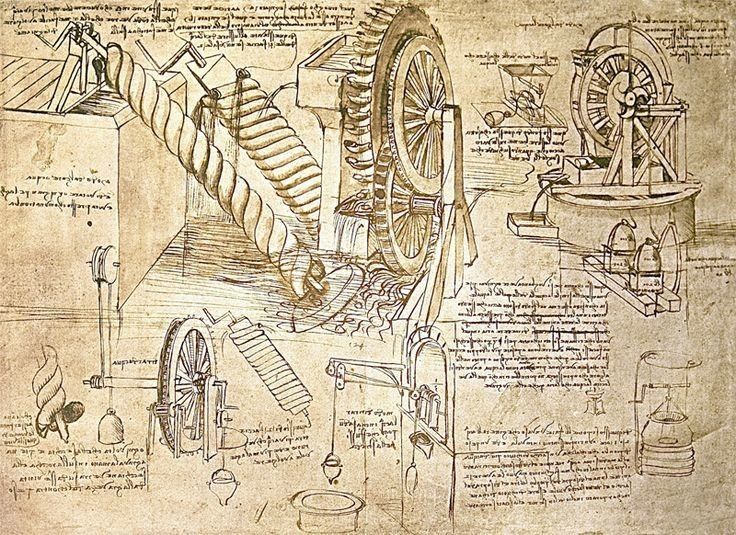

Although the term ‘user experience’ has only recently become an important design discipline, which continues to grow and evolve, the origin of thinking about the end user can be traced back to Leonardo da Vinci circa 1430. Da Vinci was asked by the Duke of Milan to help prepare an extravagant meal for a large dinner party, and being the great inventor he was, decided to think of how he could create an innovative solution to help speed up the proceedings. In his usual inventive flair, he developed a series of conveyor belts in the kitchen to transport the food from the cooks to the preparers, a large oven to cook food at a higher temperature and a sprinkler system in case there was a fire. Although this resulted in a nightmare based on the fact that the conveyor belts operated too erratically for the workers, burnt food due to the chefs unfamiliarity with the new oven and further ruined food due the sprinkler activating over the burnt food, traces of how da Vinci was trying to improve processes for the user are evident (Sullivan, 2012).

Figure 1: Da Vinci Kitchen Nightmare

More directly related to how we use the term ‘user experience’ today, at the beginning of the industrial revolution in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Frederick Winslow Taylor and Henry Ford paved the way to improve efficiencies and productivity in human labor. Corporations were on the incline and skilled workforce was on the decline, which called for advances in technology. Although being criticized for dehumanizing workers in the process, this research into the interactions between the workers are their tools personifies how we think of UX design today (UX Booth, 2013).

In 1926, the Civil War study was carried out, aimed at measuring the average dimensions including height, weight and arm-length for each of the members of the army in order to design the first airplane cockpit. Pilots were then selected based on their ability to fit into the cockpit, but due to the expansion of the air force at the beginning of World War II, hundreds of new pilots had to be recruited. This resulted in an increase of deaths due to the cockpit being designed for the average 1920’s man. Researcher and Harvard graduate Gilbert S. Daniels realised that by designing something for the average person, was literally designing it to fit nobody. From this understanding, came the science of ergonomics: the study of how to match people’s physical capacity to the needs of the job (Trufelman, 2016).

This concept was then taken up by a psychologist named Paul Fitts who served the US Air Force. ‘Fitts’ Law’ was thus developed recommending the most effective organisation of cockpit controls based on the time required to move to a target, determined by its distance and size (Strike, 2015).

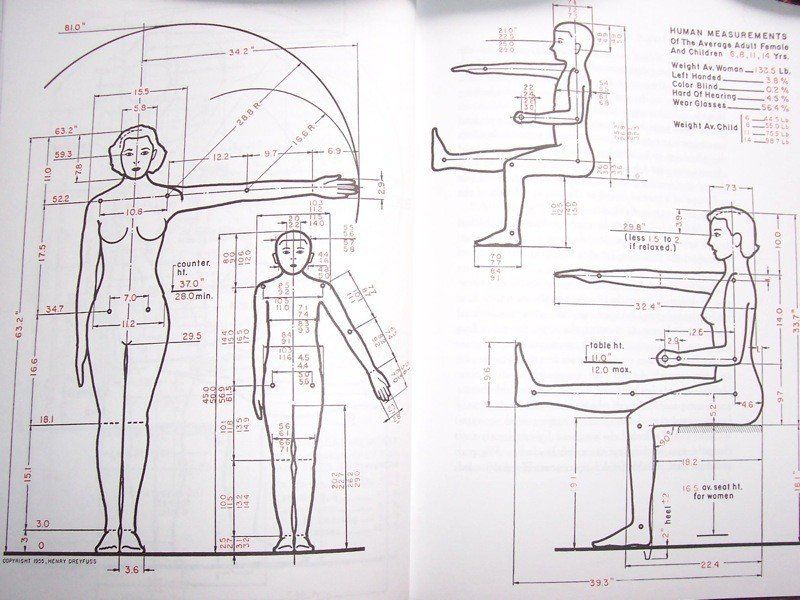

In 1955, an industrial designer by the name of Henry Dreyfuss, wrote an autobiography on design philosophy called ‘Designing for People’. In the introduction, he lays out the task of a designer, which was posted on the wall of his offices. “If the point of contact between the product and the people becomes a point of friction, then the industrial designer has failed. On the other hand, if people are made safer, more comfortable, more eager to purchase, more efficient - or just plain happier - by contact with the product, then the designer has succeeded”. This, combined with Fitts’ Law, became the basic laws of physics for UX designers (Rushdan Tari, 2015).

Figure 2: Henry Drefuss - Designing for People

The actual term ‘user experience’ was first coined in the 1990's by cognitive science researcher Dr. Donald Norman. Norman joined Apple as a ‘User Experience Architect’ to help research and design its upcoming line of human-centered products, focusing on the importance of user-centered design. During this time, he wrote the book ‘The Design of Everyday Things’ which remains highly influential for UX designers today.

Understanding User Experience

There have been many diagrams developed in order to help try and delve into the intricate world of explaining and understanding UX design (Maier, 2010).

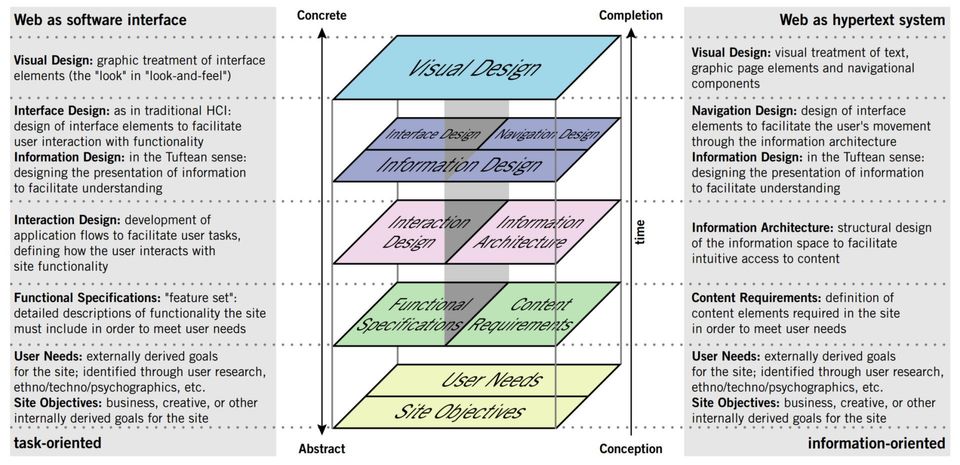

The Elements of User Design

In 2000, Jesse James Garrett attempted to capture the complexity of UX design by defining fundamental problem components that focus on design and ideas rather than tools and techniques (Jig, 2004).

Figure 3: Elements of User Design

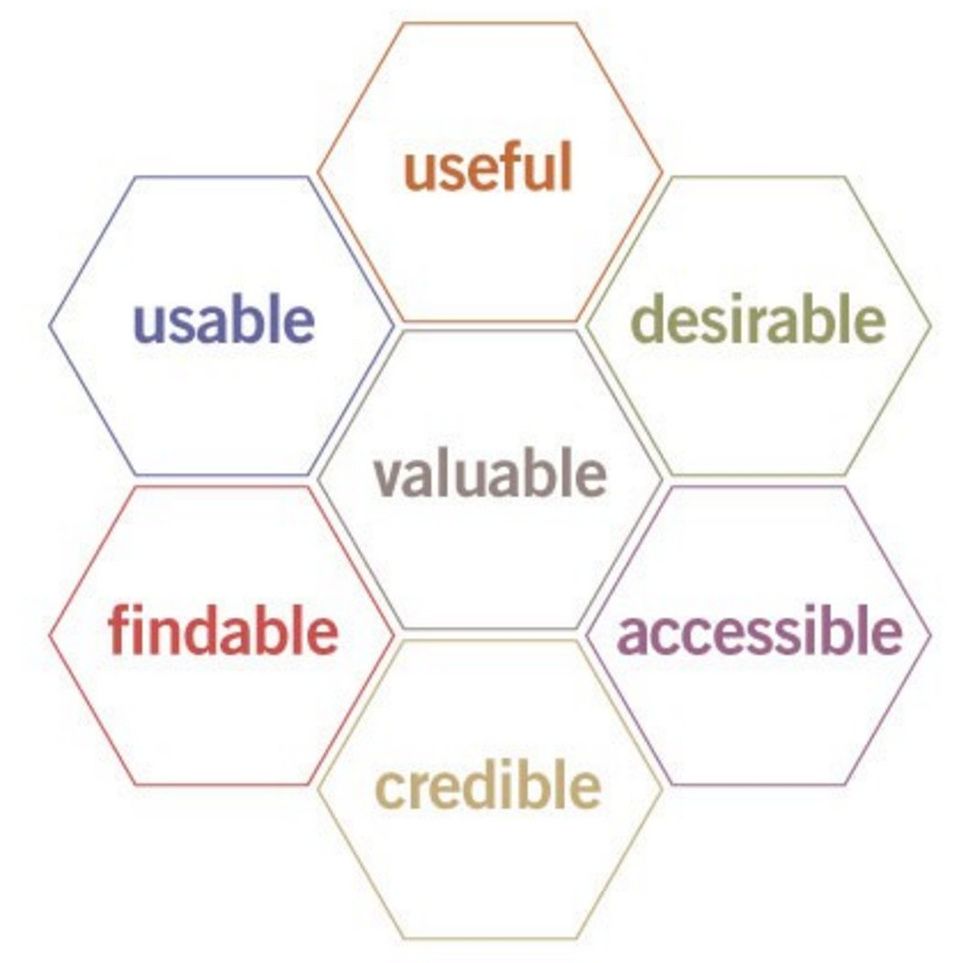

User Experience Honeycomb

In 2004, Peter Morville created this diagram to show clients the need to move beyond usability by illustrating the facets of user experience (Morville, 2004).

Figure 4: User Experience Honeycomb

Business Value of User Experience

New ParagraphIn recent years, companies have had an increased focus on keeping their users happy by investing in the research and development of user design. Investing in UX design has been proven to increase productivity, reduce costs, increase sales and return between 2 and 100 dollars for every dollar invested (Cipan, 2009). Other studies have shown that when UX is executed effectively, on average, a company’s revenue can be increased by 37% (On3 Marketing, 2014).

For websites, studies show that if a website page is slow to load, 23% of users will stop shopping and 14% of users will choose to shop at a different site, causing retailers a £1.73bn loss in sales annually (Moth, 2012). When it comes to mobile applications, currently there are over 1000 new apps submitted to the Apple App store on a daily basis. The choice is so great that if a user does not quickly have a good user experience with an app, they will most likely move on and search for another app to complete their task. If an app has poor performance, studies show that 90% of users will stop using the app and 86% of users will delete/uninstall the app (Market Watch, 2014). For businesses, studies show that 74% of people will return to the site if it has been mobile optimized but if their mobile app does not perform well, 48% of people feel that the business does not care, and 52% of people will be less likely to engage with the company in the future (Murton, 2012).

References

- Anić, I. (2015). The business value of User Experience (UX) Design. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.uxpassion.com/blog/business-value-of-ux-design/.

- Cipan, V. (2009). UX ROI: User Experience Return on Investment. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.uxpassion.com/blog/ux-roi-user-experience-return-on-investment/.

- Figure 1: Da Vinci Kitchen Nightmare. https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/736x/c2/8a/3c/c28a3c5b1323c5617414a5fadfba2c01.jpg

- Figure 2: Henry Drefuss - Designing for People. http://www.designersreviewofbooks.com/2009/05/designing-for-people/

- Figure 3: Elements of User Design. http://www.jjg.net/elements/pdf/elements.pdf

- Figure 4: User Experience Honeycomb. http://semanticstudios.com/user_experience_design/

- Garrett, J. (2000). The Elements of User Experience. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.jjg.net/elements/pdf/elements.pdf.

- ISO (2016). Ergonomics of human-system interaction - Part 210: Human-centred design for interactive systems. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:9241:-210:ed-1:v1:en.

- Jig (2004). The Elements of User Experience. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.jjg.net/elements/.

- Magain, M. and Chambers, L. (2014). Get Started in UX: The Complete Guide to Launching a Career in User Experience Design Kindle Edition. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.amazon.com/Get-Started-UX-Launching-Experience-ebook/dp/B00OL4HAOK.

- Maier, A. (2010). 8 Must-see UX Diagrams. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.uxbooth.com/articles/8-must-see-ux-diagrams/.

- Market Watch (2014). Mobile App Performance Increasingly Critical -- AppDynamics Releases 'App Attention Span' Study Which Shows Nearly 90 Percent Surveyed Stopped Using an App Due to Poor Performance. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.marketwatch.com/story/mobile-app-performance-increasingly-critical-appdynamics-releases-app-attention-span-study-which-shows-nearly-90-percent-surveyed-stopped-using-an-app-due-to-poor-performance-2014-06-12.

- Morville, P. (2004). User Experience Design. [ONLINE] Available at: http://semanticstudios.com/user_experience_design/.

- Moth, D. (2012). Site speed: case studies, tips and tools for improving your conversion rate. [ONLINE] Available at: https://econsultancy.com/blog/10936-site-speed-case-studies-tips-and-tools-for-improving-your-conversion-rate.

- Murton, D. (2012). 10 Mobile Web Design Statistics All Marketers Should Know About. [ONLINE] Available at: http://blog.marginmedia.com.au/Our-Blog/bid/87385/10-Mobile-Web-Design-Statistics-All-Marketers-Should-Know-About.

- On3 Marketing (2014). The business value of user experience – INFOGRAPHIC. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.on3software.com/business-value-user-experience/.

- Rushdan Tariq, A. (2015). A Brief History of User Experience. [ONLINE] Available at: http://blog.invisionapp.com/a-brief-history-of-user-experience/.

- Strike, T. (2015). What the heck is UX? [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.nixondesign.com/latest-news/what-the-heck-is-ux/.

- Sullivan, B. (2012). Leonardo’s Kitchen Nightmare. [ONLINE] Available at: http://boxesandarrows.com/leonardos-kitchen-nightmare/.

- Trufelman, A. (2016). On Average. [ONLINE] Available at: http://99percentinvisible.org/episode/on-average/.

- UX Booth (2013). Where UX Comes From. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.uxbooth.com/articles/where-ux-comes-from/.