The Rise of Ethics in Artificial Intelligence (Part 2: Content Ownership)

8 minute read

In my previous article 'The Rise of Ethics in Artificial Intelligence (Part 1: Privacy)', I outlined some privacy concerns that the enjoyment and convenience of our connected devices are leading to the intrusiveness of our behaviours and patterns. In this article, I will highlight some interesting stories that blur the lines between technology and humanity. All thoughts, views and comments are my own.

Technology vs. Humanity

We are constantly threading the boundaries between technology and humanity, but how did we end up here? Well we now have access to mass amounts of data. It was estimated that there was more data created in 2019 than in the entire history of the internet (Gorey, 2015). Computing power has advanced to the point now of using supercomputers that can process 200,000 trillion calculations per second (BBC News, 2018). Combining the two previous points provides a powerful platform to run the algorithms that have been developed by some of the brightest minds. The following are some examples that highlight not just the technological issues, but also human ones when it comes to technology intersecting our lives.

The Monkey Selfie

In 2011, a photographer called David Slater was traveling through Indonesia photographing a troop of macaques. On trying to get the perfect shot, he decided to set up a camera on a tripod. When he returned, he found the troop ‘monkeying’ around with his equipment – “They were quite mischievous, jumping all over my equipment. One hit the button. The sound got his attention and he kept pressing it. At first it scared the rest of them away but they soon came back – it was amazing to watch” (Morris, 2011). This resulted in probably the most amazing selfie you are likely to see.

Figure 1: Monkey Selfie

But this selfie has been the subject of a number of debates around ownership and copyright. After Slater published the image in a book, the image went viral, which lead to a complicated legal dispute in 2014 when Slater asked Wikipedia to stop using the monkey selfie image without his permission. Wikipedia refused claiming that the photograph cannot have copyrights because the monkey was the actual creator of the image (Wong, 2017). In addition to this, in 2015, the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (Peta) pushed to have the monkey “declared the author and owner of the photograph” by filing a law suit against Slater on behalf of the macaque (The Guardian, 2017). This is an interesting case, and sets the scene of how this relates to AI.

The AI Artist

In one of my previous articles, ‘Microsoft Paint – For the AI Generation’, I talked about how we can turn our doodles into masterpieces. But how about creating masterpieces without the need for a doodle? Well in October 2018, a piece of artwork that sold during an auction in Christies, made the news for a very unique reason; it was the first time that an auction house had presented a work of art created by an algorithm. It was estimated to sell for approximately $10,000 but actually sold for just over $430,000 (Christie’s, 2018).

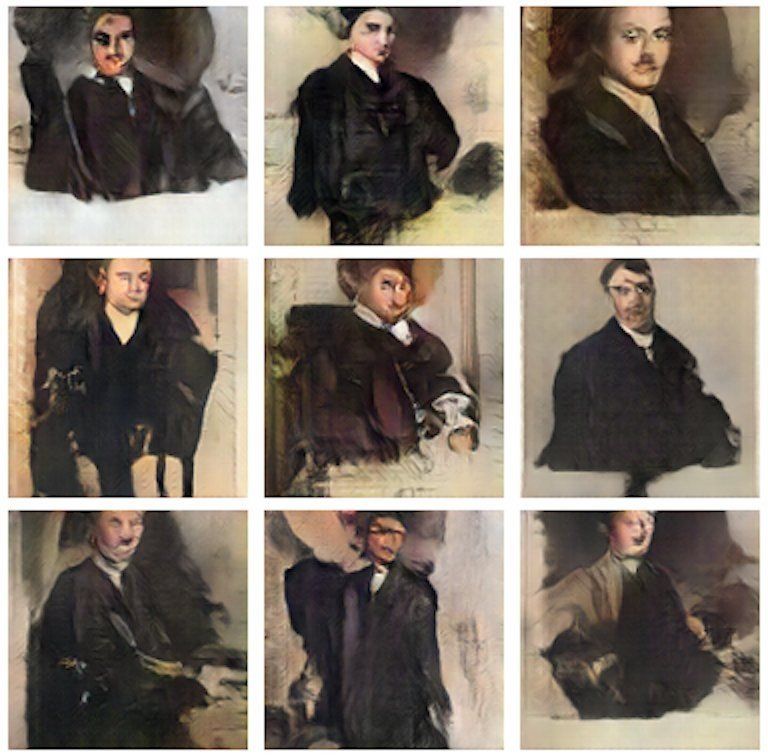

Figure 2: AI Generated Artwork - Edmond De Belamy

It all started when 19-year old Robbie Barrat, who is now currently working at a Stanford University AI Research Lab, released open-source code that utilised a generative adversarial network (GAN) to understand the relationships between different features, and as a result, would produce new material based on the data that was fed into the algorithm, some of which can be seen below from almost a year previous to the artwork that was sold at auction. In the spirit of the open-source community, Barrat’s intention was to “help and inspire” others, but when a Parisian art collective by the name of ‘Obvious’ took his code in order to make a profit, this sparked a debate around ownership and ethics. So in essence, Obvious utilised Barrat’s code, made some minor changes, fed over 150,000 pieces of art to the algorithm, and created the peace of artwork which ultimately sold for over $430,000 (Vincent, 2018).

Figure 3: Robbie Barrat Neural Network Output

This raises the question of who owns this piece of artwork? Who is the artist – is it Barrat who developed the original codebase, because without his code there would be no artwork, or is it the group Obvious, because without them amending the code and feeding the images into the algorithm there would also be no artwork? But if you compare this to how humans learn, we mimic those around us, we learn from our teachers, we put together the pieces that we like and build upon them, and we discard the rest. It’s how we create music, how we create art, how we create technology. So for this comparison, one could argue that in this case Barrat is the teacher, and the AI is the student.

AI Harmony

Using the same approach that created the artwork above, GANs can also be applied to produce digital content. In March 2019, to celebrate Johann Sebastian Bach’s birthday, Google provided a Doodle that allowed you to create a melody using piano keys on the screen. It then converted this into a musical piece in the style of Bach using a GAN that analysed more than 300 Bach compositions (Vincent, 2019).

In 2017, a British band called Shaking Chains’ took part in an algorithmic filmmaking experiment for their debut single ‘Midnight Oil’. They used a bespoke algorithm that used specific search terms in order to retrieve online video content that resulted in a different video each time the music video was played (Holmes, 2017). This video doesn’t seem to be working now, but I remember looking at it when it first came out. Similarly in 2017, the British band Muse released a music video for their song ‘Dig Down’ that changes every 24 hours. They used algorithms that scrape online video content and stitch together clips that match the lyrics of the song (Haridy, 2017). But not only can it create music and video content, it can also produce lyrics. Barrat, the same guy from the AI art above, created an algorithm to use 6,000 Kanye West lyrics and rearrange into new sequences and generate a complete song based on a similar feel (Glenn, 2017).

Final Thoughts

With the advancements in technology, if we are not careful, we will soon lose control of what’s being developed. Our machines are becoming ‘smarter’ and producing outputs that we will no longer understand. We have seen examples of utilising GANs to generate artwork and digital content. Even since the AI artist, a humanoid robot has made us question the nature of creativity by creating art that has sold for more than £1 Million (Interesting Engineering, 2019). The boundaries of art and technology are continuing to be explored by aiming to create a 3D printed painting by using all of Rembrandt’s paintings (Dutch Digital Design, 2018). At what point are we going to see complete AI generated music, novels, and screenplays hitting our charts, and how will this change concerts and red carpet events in the future? In my next article, I will talk about what is being done to ensure that this AI generated content and future applications are done in a trustworthy manner.

Until next time, I hope you enjoyed the read. GB

References

- BBC News. (2018). US debuts world's fastest supercomputer. [online] Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-44439515. (Accessed 15 January 2020).

- Christie’s. (2018). Is artificial intelligence set to become art’s next medium? [online] Available at: https://www.christies.com/features/A-collaboration-between-two-artists-one-human-one-a-machine-9332-1.aspx. (Accessed 15 January 2020).

- Dutch Digital Design. (2018). The Next Rembrandt: bringing the Old Master back to life. [online] Available at: https://medium.com/@DutchDigital/the-next-rembrandt-bringing-the-old-master-back-to-life-35dfb1653597. (Accessed 15 January 2020).

- Figure 0: Cover. [online] Available at: https://www.worldaishow.com/articles/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/world-ai-show-sm-article-3-1.jpg. (Accessed 15 January 2020).

- Figure 1: Monkey Selfie. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Macaca_nigra_self-portrait_large.jpg. (Accessed 15 January 2020).

- Figure 2: AI Generated Artwork - Edmond De Belamy. [online] Available at: https://www.christies.com/media-library/images/features/articles/2018/08/09/a-collaboration-between-two-artists-one-human-one-a-machine/edmond-de-belamy-framed-cropped.jpg. (Accessed 15 January 2020).

- Figure 3: Robbie Barrat Neural Network Outputs. [online] Available at: https://twitter.com/DrBeef_/status/1055285640420483073/photo/2. (Accessed 15 January 2020).

- Glenn, E. (2017). Listen To An AI Rap Based On Kanye West’s Lyrics. [online] Available at: https://www.thefader.com/2017/03/17/ai-rap-kanye-west-lyrics. (Accessed 18 Janyary 2020).

- Gorey, C. (2015). More data to be created in 2019 than in history of the internet. [online] Available at: https://www.siliconrepublic.com/comms/more-data-to-be-created-in-2019-than-history-of-the-internet. (Accessed 15 January 2020).

- Haridy, R. (2017). The AI-generated music video that changes every 24 hours. [online] Available at: https://newatlas.com/ai-music-video-muse/50380/. (Accessed 15 January 2020).

- Holmes, K. (2017). [Premiere] Algorithmic Filmmaking Experiment Creates a New Music Video Every Time You Play It. [online] Available at: https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/9amjy5/shaking-chains-algorithmic-filmmaking-youtube-music-video. (Accessed 15 January 2020).

- iHeart. (2018). The Complicated Story of an AI Artist. [online] Available at: https://www.iheart.com/podcast/105-techstuff-26941194/episode/the-complicated-story-of-an-ai-30087808/. (Accessed January 3 2020).

- IIEA. (2018). TOWARDS A EUROPEAN STRATEGY FOR ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE. [online] Available at: https://www.iiea.com/economics/towards-a-european-strategy-for-artificial-intelligence/. (Accessed 15 January 2020).

- Interesting Engineering. (2019). An AI Robot Artist Is Creating Art That Has Sold for More Than £1 Million. [online] Available at: https://interestingengineering.com/an-ai-robot-artist-is-creating-art-that-has-sold-for-more-than-1-million. (Accessed 15 January 2020).

- Morris, S. (2011). Shutter-happy monkey turns photographer. [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/jul/04/shutter-happy-monkey-photographer. (Accessed 15 January 2020).

- The Guardian. (2017). British photographer wins court battle over monkey selfie. [online] Available at: https://www.thejournal.ie/monkey-selfie-3594714-Sep2017/. (Accessed 15 January 2020).

- Vincent, J. (2018). HOW THREE FRENCH STUDENTS USED BORROWED CODE TO PUT THE FIRST AI PORTRAIT IN CHRISTIE’S. [online] Available at: https://www.theverge.com/2018/10/23/18013190/ai-art-portrait-auction-christies-belamy-obvious-robbie-barrat-gans. (Accessed 15 January 2020).

- Vincent, J. (2019). Google’s next Doodle uses AI to generate music in the style of Johann Sebastian Bach. [online] Available at: https://www.theverge.com/2019/3/20/18274077/google-doodle-johann-sebastian-bach-birthday-ai-machine-learning. (Accessed 15 January 2020).

- Wong, J. C. (2017). Monkey selfie photographer says he's broke: 'I'm thinking of dog walking'. [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/jul/12/monkey-selfie-macaque-copyright-court-david-slater. (Accessed 15 January 2020).